The Fractal Modulith, revisited

Quite a while ago I’ve talked about the fact that once your app ends up with 15+ services, oftentime you end up with “hidden” structure in your app that is not reflected in your codebase, which is bad because the next programmer working on the codebase will not have this hidden knowledge which will muddy up the codebase further.

Like, your “services” directory is a flat structure in pretty much any framework, but in actuality, you have services depending on other services, often in a hierarchical manner. My proposed solution was to nest applications inside applications, to make this structure explicit.

Since then I’ve come up with the absolute minimal example of this pattern, which you can expore at this StackBlitz.

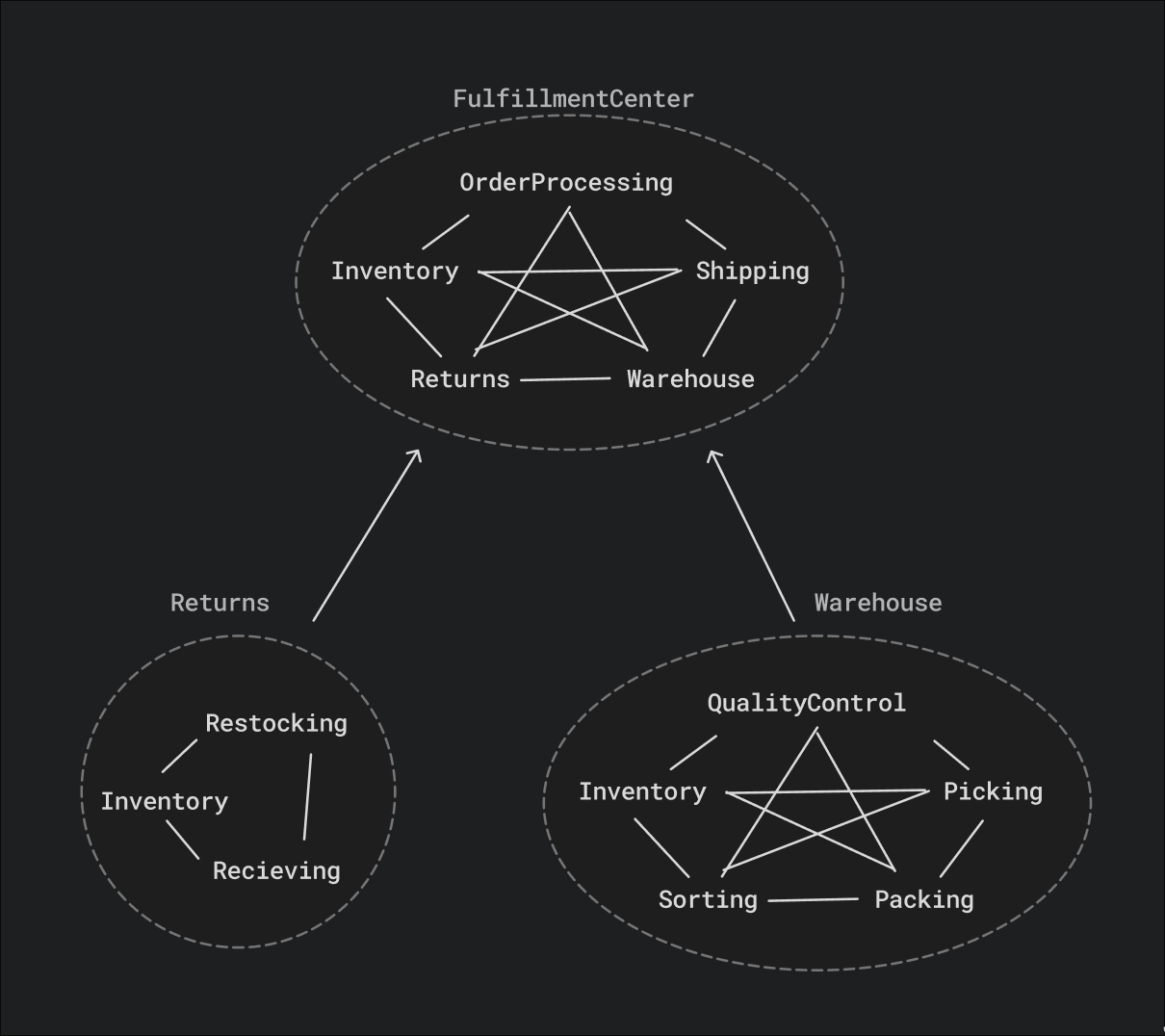

Here we’ve modeled a fulfillment center application that contains services (Inventory, OrderProcessing, Shipping),

and also sub-applications (Returns, Warehouse) that in turn contain their own services. The sub-applications

have access to the services of their parent application, and can use them like their own. This is useful because every

sub-sub-app will likely need access to core services like databases and metrics for example, so you just pass those down

from the top-level application.

The folder structure is very simple, applications have two folders: app containing the app definition, and service,

containg a folder for each service or sub-application.

The _framework folder contains the minimal implementation of the fractal modulith pattern. It’s basically two type

definitions, though I’ve had to add a single bit of framework magic, to ensure that services are only started once.

I’ve also shipped a logger for nice colorful logs but this is of course optional.

But before I give you more thoughts about why I think this is useful, let’s take a step back first. We’re doing basic research on this blog after all.

What even is an application, and what is a service?

My opinion on OOP is that while horribly overused, it is useful for some things, and one of these things I would like to call “routing”. In my world view, the job of a service is to call other services to gather data, and once you’ve gathered all the data, you hand it off to the functional core of your application, and all the business logic happens there.

As such, we can clearly delineate the narrow responsibilities of services and applications:

- An application is a service that contains a list of services. These services can all see and use each other.

- A service is a class that can be started and stopped.

That’s it. The fractal structure emerges naturally from these two simple definitions. ob

Trees and Graphs

This is also a blog about mathematics after all so let’s look at some diagrams.

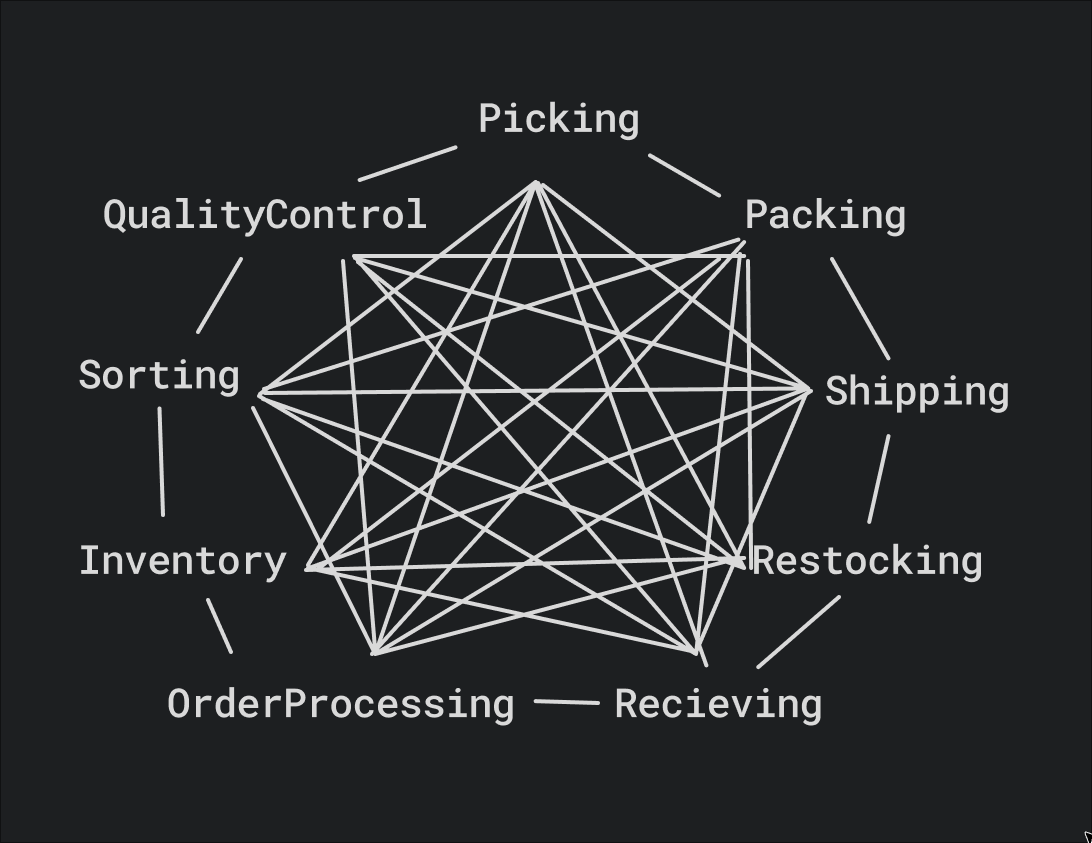

When I say “an application’s services can all see and use each other”, this is what’s commonly referred to as dependency injection. If we create a diagram of each service in a non-fractal application and trace which services are allowed to call which other services, we end up with a fully connected graph:

And since every service can see every other service, even though most of these connections aren’t realized in your current codebase, you just know that one dev during crunchtime is going to make use of the possibility and create a tangled mess of dependencies by injecting everything everywhere.

The fractal modulith pattern transforms this fully connected graph into a tree of graphs; the tree is a tree of applications, and each application is a fully connected graph of services.

A fully connected graph of n services has O(n²) connections, while our fractal modulith has O(n) connections, if we assume each application has around 5 services, meaning that with a growing number of services, the fractal approach will quickly show its benefits.

Migrating from a monolith to a fractal modulith

If you have a flat services directory and would like to figure out which services belong together, then this is actually a very well-studied problem of finding so-called strongly connected components in a directed graph — look at the image on the wikipedia article, it looks exactly like what we are doing here! Tarjan’s algorithm is a great algorithm to find these components in linear time, but in practice you’ll probably just do this manually.

Enforcing app boundaries

In my code example above, services in sub-applications can indirectly access services in parent applications, and you could technically reach every service from everywhere else. So how do we enforce that this doesn’t happen? Maybe ArchUnit tests? Confluence pages with architecture guidelines?

I would argue no! As I have argued before, the best way to enforce architecture is to add friction to doing the wrong thing, and make doing the right thing easy. Developers aren’t malicious after all, but they choose the path of least resistance just like the rest of us.

The fractal modulith does this auomatically. Say you are two applications deep in ReturnsApplication and suddenly

realize you need to call a method in a “great uncle service” like SortingService. To do this the “wrong” way you would

need to call app.parent.parent.Warehouse.services.Sorting,

which is so horrible to look at that no developer would ever do this, and no code reviewer would ever approve it.

The right (and natural) thing to do is to move the SortingService up into the most recent common ancestor application,

and then pass it down so the service that needs it can just write app.services.Sorting.

We are naturally incentivising developers to keep the tree structure intact, an no further architecture enforcement is needed.

And if we ever would like to move ReturnsApplication into its own microservice, this helps us easily see what we need to migrate:

Just follow the tree upwards, all the adjacent tree nodes are not needed for the service to work.