Type Systems #25: The Lambda Iceberg and Lambda Cube

(This is part 25 in a series on type systems. You can find part 24 here .)

Hey I had a blast writing this series, hope you enjoyed it too!

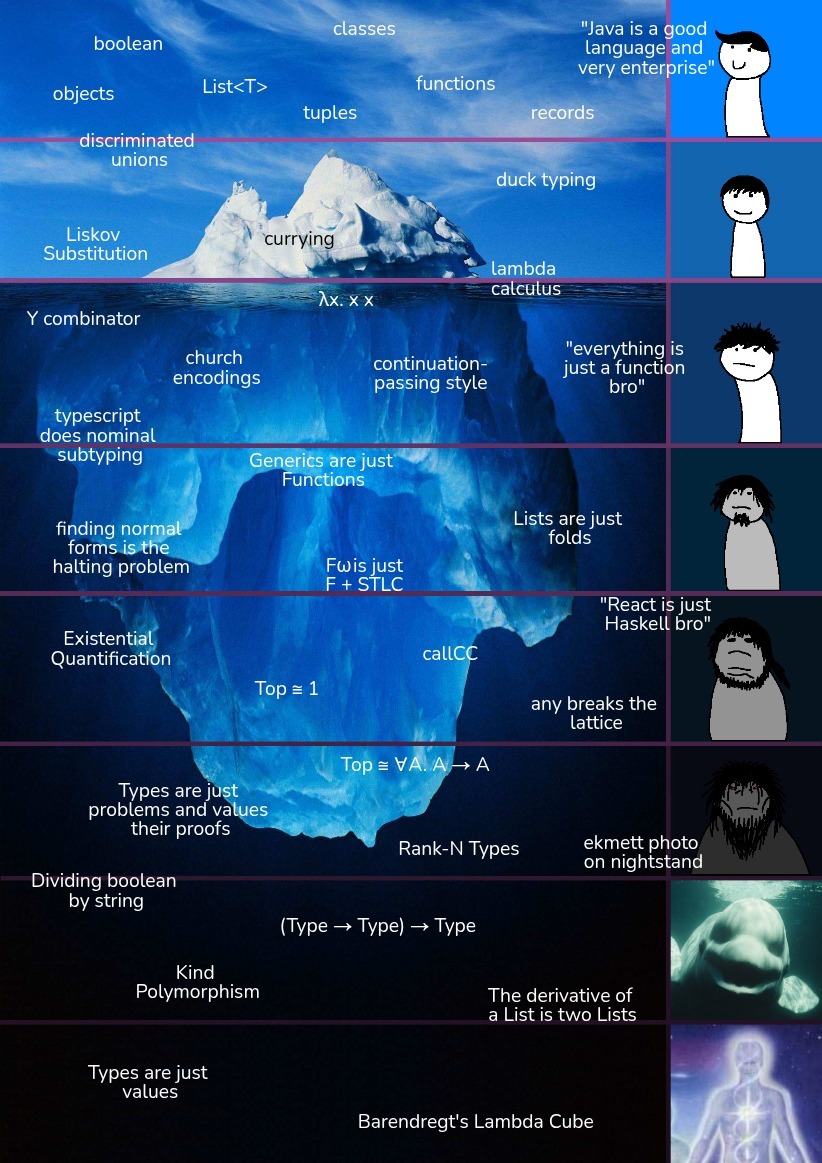

As a small Christmas gift to you all, I’ve distilled all the things we have discussed into meme format, so you can send it to all your type theory friends. I present to you: The Lambda Iceberg!

On a more serious note.

Why the hell would we need all this? Haven’t we been writing javascript and python code just fine? What do I need kind polymorphism for, or dependent types? Can we not leave that to the nerds?

Well. I’ve mused about AI requiring stricter type systems on this blog before — if we can put tighter constraints on the code we want the AI to generate, results will be less sloppy and more predictable. Other people seem to mirror the sentiment, just this week the article Prediction: AI will make formal verification go mainstream was trending on Hacker News.

At the moment, we use prompting to steer AI, but we do all know how hit-and-miss that can be… AI slop is called AI slop for a reason.

I believe that types will be the common language that connects programmers or “prompt engineers” with AI systems in the future, as they are precise, unambiguous, and at the same time expressive enough to capture complex constraints.

So, now more than ever, it seems prudent to learn about advanced type systems; as AI takes over the lower levels of programming, humans will naturally move up the abstraction ladder. Nobody will be writing javascript in a few years — I’m already using copilot for everything — and descriptions of what we want to build will be all that remain.

One could even say that with AI generating code, and you refining types depending on AI output, that you are the formal verification system, using “dependent” types to guide the AI to produce correct code.

Parting Thought: Barendregt’s Lambda Cube

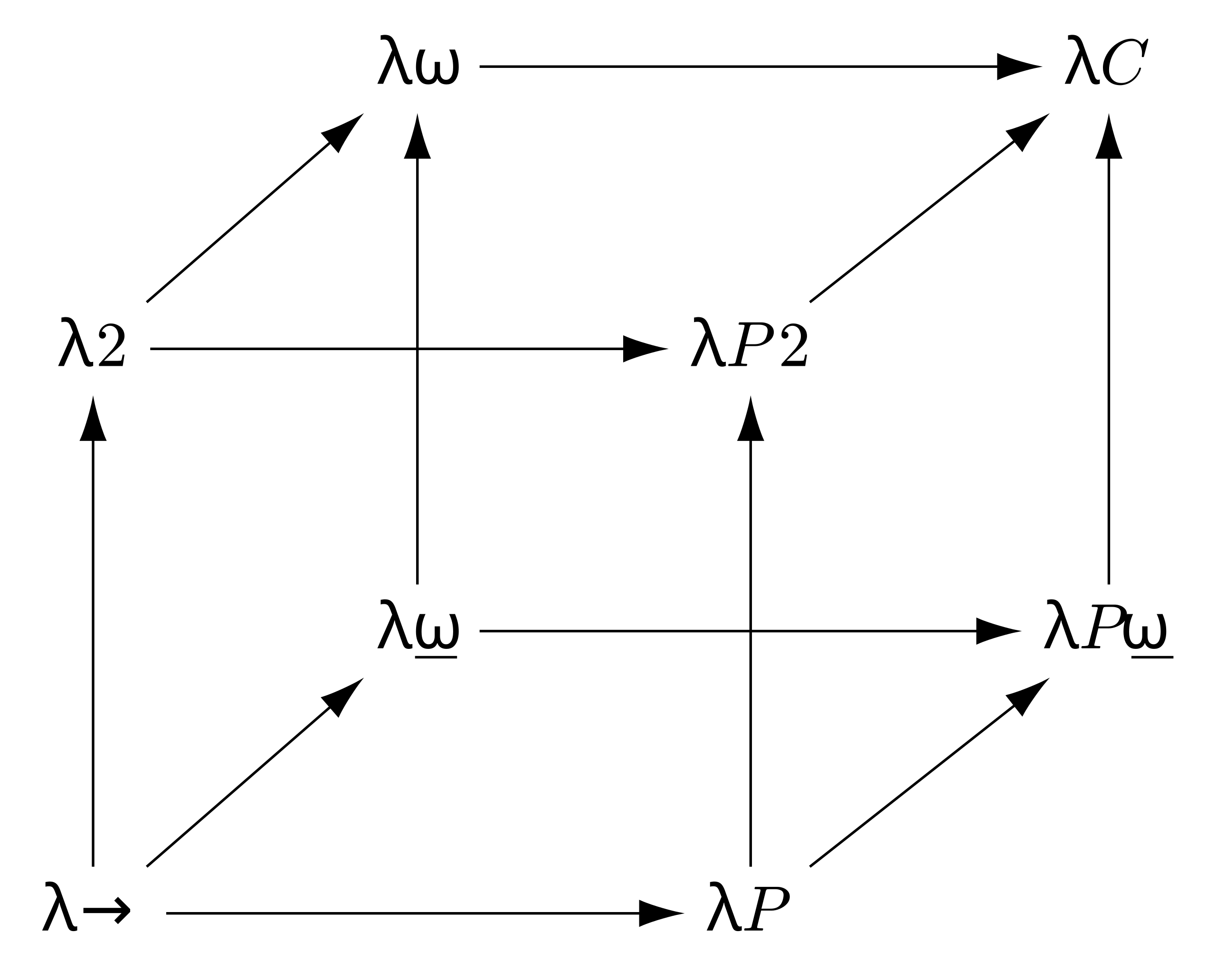

There are probably more type systems than there are type systems researchers, but the canonical type systems hierarchy that I have stuck to this series is Barendregt’s Lambda Cube.

It organizes lambda calculi by expressiveness along three axes, and explores how the calculus of constructions can be arrived at by incrementally adding features to the simply typed lambda calculus. This past month, we’ve taken one particular path through the cube:

λ→is simply typed lambda calculus.λ2is System F, adding generic typesλωis System Fω, adding kindsλCis the Calculus of Constructions, adding dependent types

There are other paths through the cube as well, but ours is

the most natural one. The other type systems are interesting in their own right —

for example λP adds just dependent types to the simply typed lambda calculus but

not generics or kinds — but they are mostly of theoretical interest.

And λC is really the pinnacle of type system expressiveness; there is no obvious

way to go any further. There exists for example the Calculus of Inductive

Constructions (CIC) that underpins Coq, but it doesn’t give more expressive

power over λC, just more convenience.

Now.. we’re really reaching the boundaries of my knowledge here, but as I understand, not

all theorems in mathematics are provable by constructive proofs, which is what

the Curry-Howard isomorphism gives us access to. So there will always be

mathematical truths that are outside the reach of any type system, that are

provable under for example the set of axioms known as Zermelo-Fraenkel set

theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC). ZFC is provably more expressive than

λC or any other type system we can come up with, because the axiom of choice

gives us access to non-constructive proofs.

And the real real ceiling of course is Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, which state that any formal system that is expressive enough to do arithmetic, and is consistent (i.e. does not both prove a statement and disprove it) is necessarily incomplete, meaning there are always true statements that cannot be proven within the system.

The Calculus of Constructions sits right at this boundary — adding more expressiveness to it would make it inconsistent in some ways. This can be desirable; for example, allowing general recursion makes a type system inconsistent and allows you to create proofs of false statements, which is bad, but obviously any practical programming language needs general recursion to be useful.

Either way this gives us no clear path forward to even more expressive type systems, as for everything gained, something else is lost. This makes the Calculus of Constructions the sweet spot for both theoretical exploration and practical use, and the lambda cube a natural visualization of type systems — from the most simple to the most expressive!

With our newfound knowledge of the Calculus of Constructions and the Lambda Cube, I’ll release you back into the wild. We’ve reached the end of this series on type systems; to be honest writing a blog post every day for almost a month was quite a challenge, but time flies when you’re having fun eh :D

If we ever want to dive deeper into type theory in the future, maybe I’ll do another series like this one — there’s still so many topics that I didn’t have the time to cover here. Monads, GADTs, Category Theory, Linear Types, Hindley-Milner Type Inference, Martin Löf Type Theory, Homotopy Type Theory (haha probably not that one), the list really is endless.

For now however, let’s stop with all the thinking. Go drive some cookies into your gut, will ya! Merry Christmas and see you around next time :)